Extract from Chapter 8

The porter pulled the interior night bell. The hospital in Averno was conducted by the brothers of the Order of the Holy Compassion of Jesus, and after some moments a monk approached along the outside cloister.

He moved silently on sandalled feet, the grey of his cloth merging with the shades of night. The cowl of his habit was raised. The flaming pitch torches set at intervals along the wall flung dark shadows on his face.

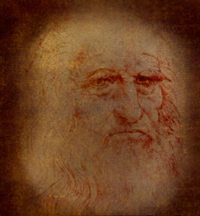

This man introduced himself as Father Benedict, the monk in charge of the mortuary. He regarded both my master and myself with interest. Then he took the Borgia pass and the magistrate’s order and read them closely.

‘This document, signed by Cesare Borgia . . . Il Valentino, the Honourable’ – was there a hesitation upon that word? – ‘Duke of Valentinois and Prince of Romagna, gives leave for you to access the castles and fortified houses in the Romagna and other parts under his domain.’

‘That is so.’ The Maestro inclined his head.

The monk held up the parchment. He read unhesitatingly:

The monk held up the parchment. He read unhesitatingly:

‘This Order is to all our lieutenants, castellans, captains, condottieri, officers, soldiers and subjects, and to any others who read this document.’

‘NOTICE THIS:’

‘Our most beloved Architect and General Engineer, Leonardo da Vinci, who bears this pass, is charged with inspecting the palaces and fortresses of our states, so that we may maintain them according to their needs and on his advice.’

‘It is our order and command that all will allow the said Leonardo da Vinci free passage, without subjecting him to any tax or toll, or other hindrance, either on himself or his companions.’

‘All will welcome him with amity, and allow him to measure and examine any things he so chooses.’

‘ To this effect, we desire that delivered unto him should be any provisions, materials and men that he might require, and that he be given any aid, assistance and favour he requests.’

The monk raised his eyes. ‘This is not a fortified building.’

‘Yet it is under his rule now,’ my master pointed out.

‘We are very aware of this.’ The monk spoke quietly.

There was a silence.

There was a silence.

The brutality of Prince Cesare Borgia’s regime and its enforcement by his governor in Romagna, General Remiro de Lorqua, was becoming known in all parts of Italy. This Remiro de Lorqua, in effecting the prince’s instruction to impose civil order locally, while the Borgia armies conquered and subdued the rest of the region, had caused widespread terror throughout the area. His methods of public torture and execution intensified the fear and hatred of the name of Borgia.

It would be a brave man who sought to oppose so ruthless an overlord. Brave monk, braver than I knew. The last sentence of the Borgia document, which he had not read out, said: Let no man act contrary to this decree unless he wishes to incur our wrath.

‘It would please me to make a donation to your funds,’ my master suggested.

But this mortuary monk was a brother of the Holy Compassion Order, whose reputation also spread wide. Established during the Crusades by a devout knight named Hugh, they were enjoined by their founder to care for anyone in need of medical care. This good knight, doctor, soldier and, latterly, saint would not allow any distinction between men and women, civilian and army, Infidel and Christian. Braving the arrows of both sides, and without payment from either, he tended the hurt and wounded where they fell on the battlefield. At home his monks nursed the poorest of the poor, the victims of plague and pestilence, the beggars and the penny whores. Unlike others they turned no one away, not even those for whom the road was home. Theirs was a true vocation, not like the secular clergy who joined the Church for personal profit. There was no bribe that could corrupt this monk, no threat that he feared. He walked with death many times every day.

He ignored my master’s offer and said, ‘If you are engaged in engineering studies, what interest do you have here?’

‘Is not the human body the most perfect piece of engineering constructed?’ my master asked him.

The man held the Maestro’s gaze for a long moment, and finally replied, ‘That is your purpose then? A study of the human body?’

‘Yes. Most sincerely it is. I am an engineer, and a painter.’

‘I am familiar with your name, Messer da Vinci,’ the monk interrupted. ‘And your famous works. I have seen your fresco of the Last Supper at the Dominican monastery in Milan, and your cartoon of the Virgin with the Christ Child and Saint Anne in the Church of the Annunciation in Florence. The images you have produced are masterpieces . . . with God’s grace.’

‘Ah!’ My master regarded the monk, then asked thoughtfully, ‘You are interested in how Scripture can be illustrated by man, through visual art?’

‘Messer da Vinci,’ the monk replied, ‘it is said that your works have many codes and symbols contained within, and that we should seek to find their true meaning.’

Previous Extract from the Medici Seal - Next Extract from The Medici Seal